AstraZeneca vs. EU: It also matters what (and who) is not in the contract

What can we learn from the vaccine delivery spat about contract negotiations?

During the Trump administration, a senior FDA official famously compared the global allocation of vaccines against the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 to oxygen masks dropping inside a depressurizing airplane: “You put on your own first, and then we want to help others as quickly as possible.”

The nations on this side of the Atlantic are certainly scrambling for masks at the moment. One year ago I argued that the Coronavirus "forces even friends to negotiate survival". For once, I would have preferred to be proven wrong. In this post I want to explore what we can learn from the spat between the EU and AstraZeneca about the non-delivery of the ChAdOx1 nCov-19 vaccine. The EU believes it has the right to receive the vaccine under the current circumstances. AstraZeneca takes the opposite view. While we thankfully do not have to settle that question, we can learn from exploring it.

What I think we can learn is that it not only matters how well a contract is drafted. Just as significant is what (and who) is not included in it. And what should have been included, at least from a European perspective, is a clause that addresses the likely competion for vaccine allocation.

The spat

In January 2021, Anglo-Swedish pharma giant AstraZeneca announced delivery bottlenecks concerning its vaccine — but only for the EU. The situation has gotten worse since then. On March 8, Ursula von der Leyen, the president of the European Commission, declared that the company had "delivered less than 10% of the amount ordered by the EU for the period from December to March." She said that the European Union had expected to receive 100 million vaccines from the company by now. So there appears to be a shortfall of 90 million doses.

But AstraZeneca´s CEO Pascal Soriot told Italy's La Repubblica already in January that the company was under no obligation to deliver: “Anyway, we didn't commit with the EU, by the way. It's not a commitment we have to Europe: it’s a best effort, we said we are going to make our best effort. (…) But our contract is not a contractual commitment. It's a best effort. Basically we said we're going to try our best, but we can't guarantee we're going to succeed.”

AstraZeneca had also agreed to deliver 100 million doses to the UK, where so far no shortfalls have occurred. And Soirot explained that the company will not use vaccines manufactured in the UK to make up for the delivery shortfalls vis-à-vis Europe.

But that is exactly what the EU demands - that AstraZeneca deliver UK-made doses to fulfill its contractual obligation. The EU, according to media reports, is particularly irritated because it had paid AstraZeneca hundreds of millions of euros in advance in order to expedite production ahead of the vaccine's approval. EU officials are reported as pointing out that EU money went into upgrading the facilities in the UK. And a member of the European parliament reportedly emphasized that the UK had benefited from AstraZeneca´s supply chain on the continent: “Until a few days ago, the vaccine destined for the UK was still being bottled in the German city of Dessau.”

So, what does the contract say? Experts, as you can imagine, disagree. Some argue that AstraZenca cannot justify the non-delivery of UK-manufactured vaccine. Others argue that it can. If AstraZeneca has to deliver UK-made vaccines to the continent, then it currently is in breach of its contract. But by remedying that breach it may very well violate its obligations vis-à-vis the UK. Vaccines, just like airline oxygen masks, are currently limited.

Before I offer my interpretation of the contract, I would like to make two disclaimers. And I think we have to look at the big picture of what, regardless of the specific spat at hand, the EU negotiators have achieved. The disclaimers: While the contract is publicly available, it is partly redacted. Which means that we have to base our analysis on an incomplete document. Furthermore, the contract is subject to Belgian law. While I have negotiated plenty of international contracts, I am not a Belgian lawyer. Which means that my interpretation might be wrong.

The Big Picture

When we look at the big picture, it is clear that the European Union did a stellar job last year. As The Lancet points out, it has so far concluded contracts for COVID-19 vaccines with Moderna (160 million doses), Sanofi-GSK (300 million doses), AstraZeneca (400 million doses), Johnson & Johnson (400 million doses), CureVac (405 million doses), and Pfizer–BioNTech (600 million doses) – and three of these vaccines have already been approved worldwide.

Looking back to last summer it is tempting to become a victim of hindsight bias. It is easy to take for granted what the EU has accomplished. But when these contracts where negotiated, nobody knew if any of the vaccines would work or could be produced. Not the EU and not the pharmaceutical companies. Hence no company would have agreed to an unconditional delivery obligation. A promise of anything more than “best” or “reasonable efforts” could, I think, not have been taken seriously. AstraZeneca did not make such a promise, neither to the EU nor to the UK.

Nevertheless, by concluding the contracts, the EU has made sure that there will be enough vaccine for all of its 450m citizens, in all 27 member countries in 2021. As von der Leyen emphasizes, going about it any different way would have been “a catastrophe for Europe.” (“Wir stehen im Sturm” February 18, 2021, Die Zeit, in German, subscription required). In theory, every country could have done what the UK has done. It could have declared emergency approval of the vaccine and procure it unilaterally. But consider the predicament in which the continent would be if its 27 nations had chosen to go it alone. The damage of (real or perceived) nationalism was apparent during the Euro crisis. Imagine what would have happened if some countries would have secured vaccines at the expense of their neighbours. Or secured them faster. Or more of them. Or better-quality ones. Would they not be accused of letting their neighbour’s citizens fall ill and die? If that had happened, for all I know, the European project might be over. It is the EU negotiators who have averted that danger. And they did not stop there. The purchase agreements will allow Europe to share the vaccine with low and middle income countries even beyond the neighbourhood, through organizations such as COVAX. The merit of the EU negotiators´ work cannot be overstated. With that in mind we can explore the AstraZeneca contract.

The EU´s view

So, what is the contract about? According to the recitals, it is for the production, purchase and supply of the ChAdOx1 nCov-19 vaccine (“Vaccine”) in the European Union (the “EU”). (Here is the contract, partly redacted).

And the “EU” does not include the UK, as Article 5.4 makes clear.

As you can see, Article 5.4 stipulates that the Vaccine is to be manufactured at sites located within the EU and the UK. A subset of the Vaccine will be supplied to the European Union, according to the recitals, in the form of “Initial Europe Doses”, and potentially in the form of “Optional Doses”:

The Initial Europe Doses, which are already defined as being the result of “Best Reasonable Efforts”, will be supplied only on the basis of AstraZeneca´s “Best Reasonable Efforts”, as Article 5.1 clarifies:

What these “Best Reasonable Efforts” are is helpfully set out in the definitions:

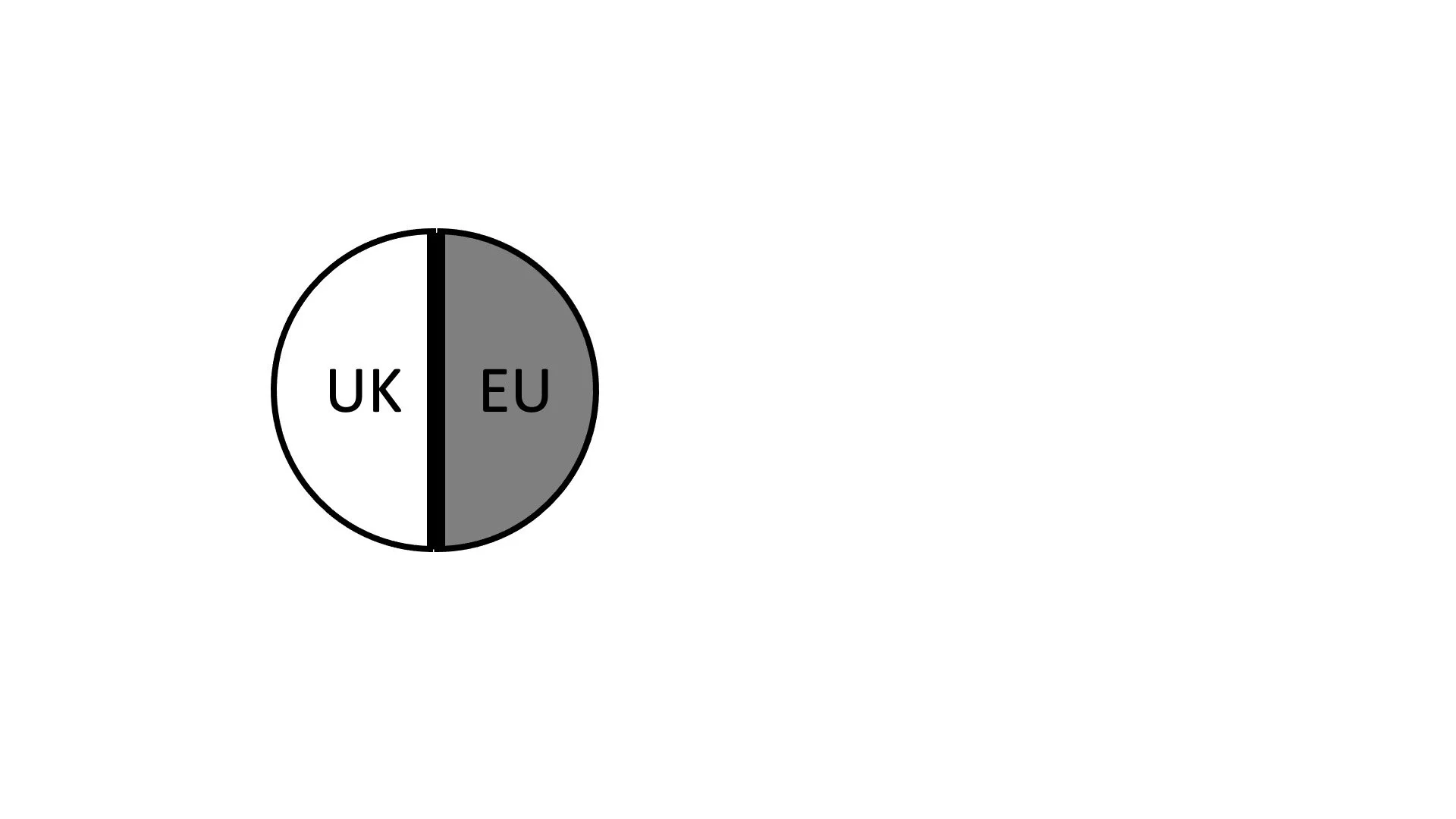

We can therefore visualize the Vaccine as follows. The circle represents the totality of the Vaccine which is manufactured both in the UK and the EU. Out of this totality, deliveries will be made to both the UK and the EU (and, presumably, third countries, which we disregard for our purposes). The two halves of the circle show these deliveries. Some will go to the EU, and some to the UK. While AstraZeneca may also supply “Optional Doses” and even “Additional Doses” to the EU in accordance with Article 5, we focus only on the Initial Europe Doses about which the contract primarily is.

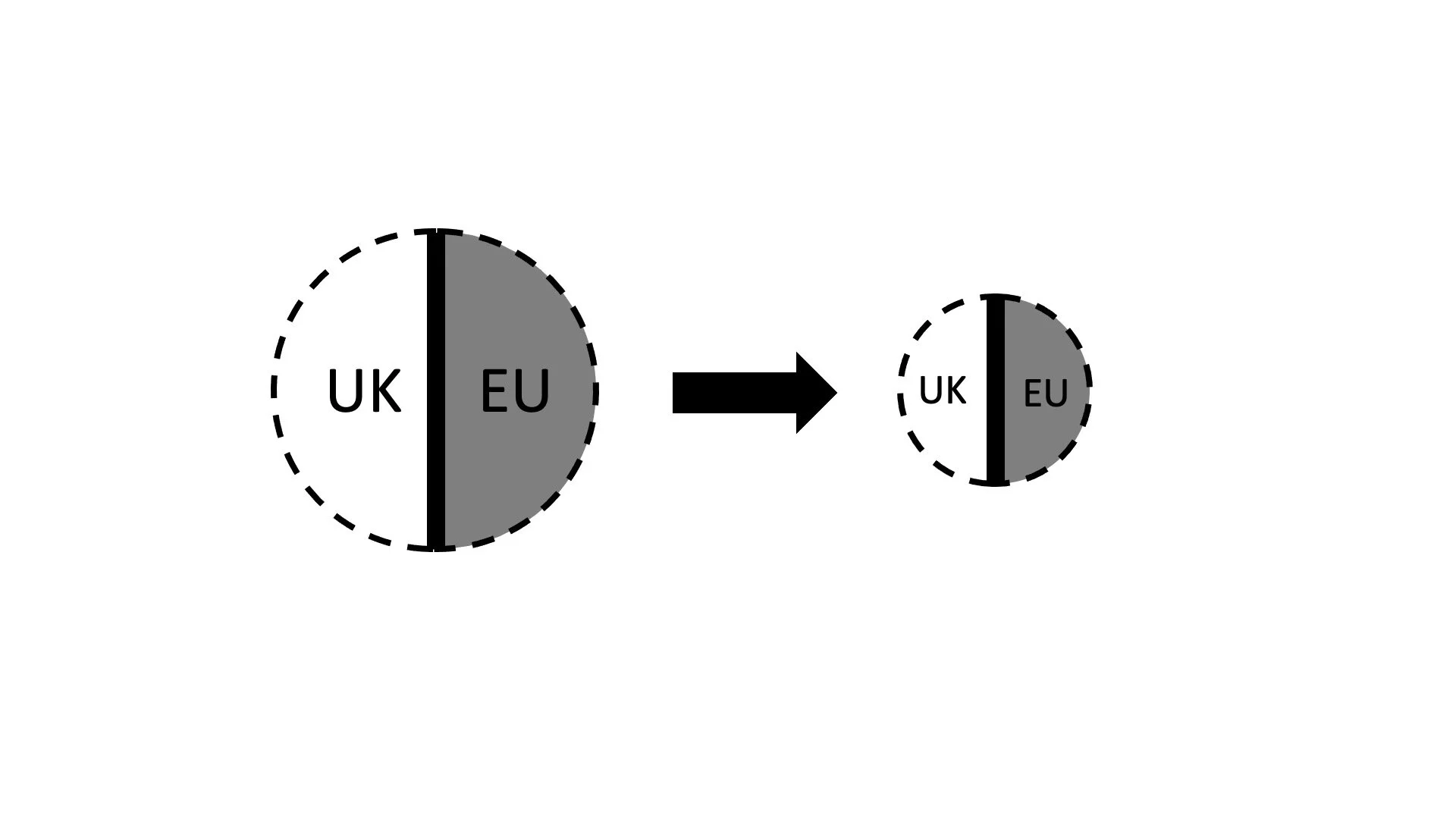

When looking at the drawing, a question springs to mind: Isn´t there the danger that AstraZeneca may be limited in its Best Reasonable Effort deliveries to the EU by what it will deliver to the UK? Figuratively speaking, could not the UK part of the circle “eat into” the European part? The contract provides an answer to that question. No, such a danger does not exist. It is ruled out explicitly by Article 13.1 (e):

In the first half of the sentence AstraZeneca warrants that it is “not under any obligation, contractual or otherwise, to any Person or third party in respect to the Initial Europe Dose.” AstraZeneca, in other words, has not promised even parts of the dose to others. And, without any indication to the contrary, that is true for the Vaccine irrespective of where it was manufactured.

In the second half of Article 13.1 (e), AstraZeneca promises even more. It is under no obligation, contractual or otherwise, that conflicts with or is inconsistent in any material respect with the terms of this Agreement or that would impede the complete fulfilment of its obligations under this Agreement. In other words, none of the obligations it may have vis-à-vis the UK stand in the way of complete fulfilment of this contract. AstraZeneca´s promise explicitly extends to non-contractual obligations. This is significant. Not just because the UK´s own purchase agreement with AstraZeneca was signed only afterwards (the next day). But also because government´s power to oblige companies goes beyond the merely contractual. Michael Wheeler of Harvard´s Program on Negotiation emphasized the clout of government in a recent blog post on the Covid vaccination deal between Merck and Johnson & Johnson. The White House had brokered that deal. Michael assumes that government had, among other things, used its “muscle, resources, and the bully pulpit”. “Merck and J&J are huge companies with lots of clout, but both need to be in the good graces of the government. We may learn later how much arm twisting was involved, if any. Explicit threats probably weren’t necessary. In this context, a raised eyebrow or a prolonged stare might have been clear enough to remind company leaders of possible consequences if they failed to cooperate.”

This is no less true in our context. After all, AstraZeneca has its corporate headquarters in Cambridge, and the Vaccine has been developed by Oxford University. We can safely assume that the UK was no less keen on receiving the Vaccine than the EU. What does all that mean? I believe that the picture which emerged in the head of the EU negotiators might have looked like this. The UK´s share of the Vaccine, irrespective of where it is manufactured, would not eat into the EU´s share. Even if there would be a supply problem, it would affect everyone equally.

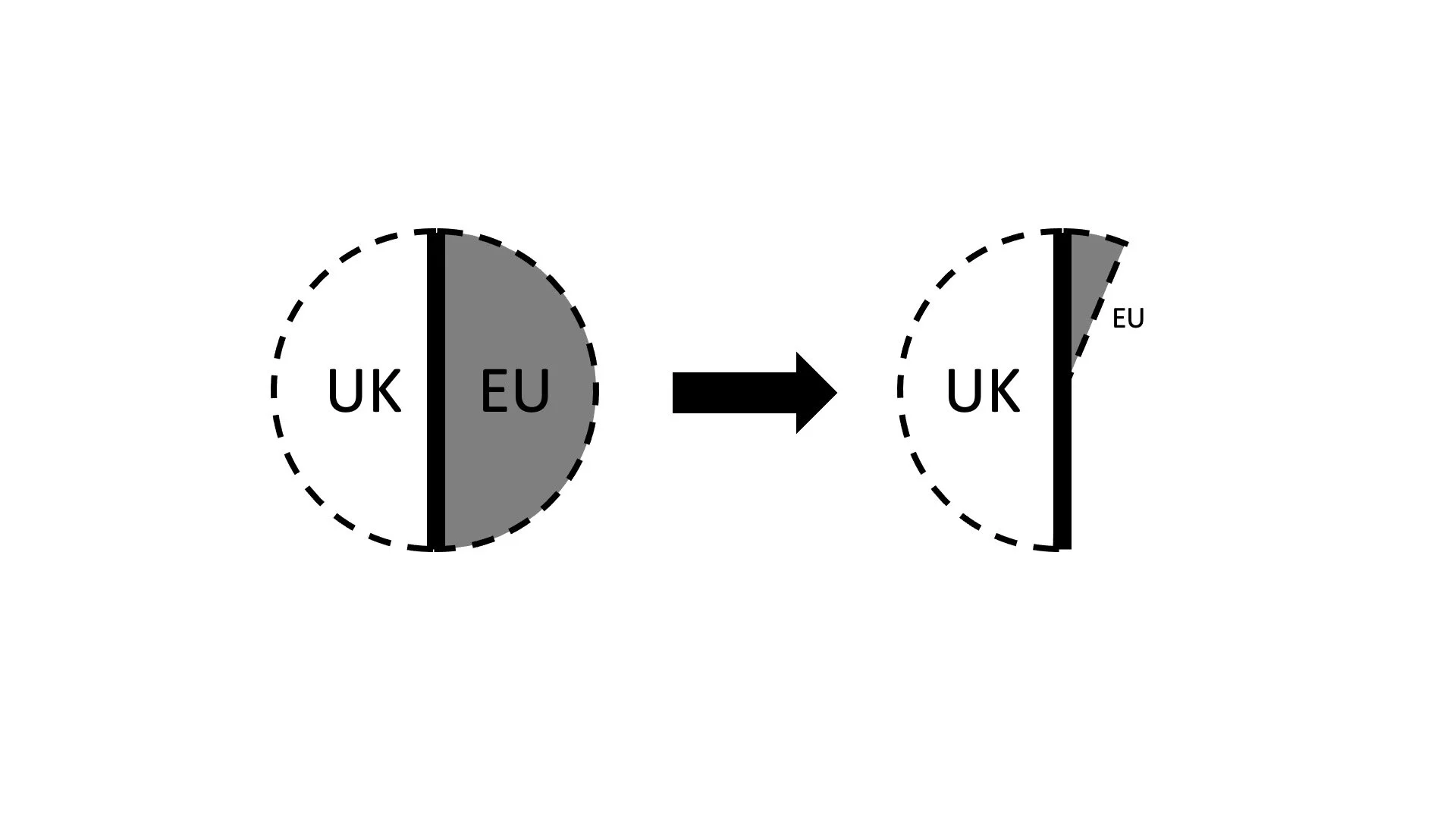

AstraZeneca´s View

The EU´s understanding is, as we know, not shared by AstraZeneca. Its CEO made clear that the company will not use vaccine manufactured in the UK to make up for the shortfalls in European deliveries. He explained that an earlier agreement prevents AstraZeneca from doing so: “The UK agreement was reached in June, three months before the European one. As you could imagine, the UK government said the supply coming out of the UK supply chain would go to the UK first. Basically, that's how it is.” Now, it is not clear to me what this agreements entails. To the best of my knowledge, it has not been made public. Either way, according to AstraZeneca, it stands in the way of European supplies. On March 11, Sweden’s vaccine coordinator, Richard Bergstrom, reported according to Bloomberg´s, that he had been told by the company they they won’t be able supply the expected doses “as there are export bans from the U.S. and India, and contractual obstacles to sending doses from the U.K.”

Which brings us the the UK´s view.

The UK´s View

The UK seems to share AstraZeneca´s view. Yes, The Economist reported that, on January 26th Britain, fearful that the Europeans might cut off its imports of the Pfizer vaccine from Belgium, warned of the perils of “vaccine nationalism.” But these perils apparently do not warrant reciprocity. “It later emerged that the EU wanted AstraZeneca to compensate for shortfalls in European factories from its British facilities.” Since then, as The Economist dryly noted, “Britain has not repeated its appeals for cross-border solidarity.”

Health Secretary Matt Hancock leaves no doubt in the matter: "I wasn't going to settle for a contract that allowed the Oxford vaccine to be delivered to others around the world before us. I was insisting we could keep all of the British public safe as my primary responsibility as the Health Secretary."

Lessons Learned: A missing clause and a missing party

So, what can we learn from all this? I think that the current situation could have been anticipated. What the EU should have done is to address the possible competition head-on. How? First, by including a provision which obliges AstraZeneca to reserve production capacities for Europe. And then to make sure that this promise comes from the entity that can, in fact, make it.

This, in effect, is what the UK has done. In Article 4.2 of its contract it received AstraZeneca´s representation that the company´s UK facilities could manufacture the promised doses (“AstraZeneca represents to the Purchaser that, to AstraZeneca´s knowledge, the Facilities for the UK Supply Chain will be appropriate and sufficient for the Manufacture and Deliver of the Conforming Product in the volumes that are the subject of the Order and in accordance with the terms of this Supply Agreement”). And that contract was made with AstraZeneca UK Limited - not, like the European contract, with AstraZeneca AB of Sweden.

Which brings us back to the disclaimer, and to the big picture. I do not know if what I am suggesting is perhaps included in another agreement. And even if that was the case, we would still face today´s production shortfall. But, at the very least, it would have saved the EU, AstraZeneca, and the UK from the problematic spat in which they find themselves today.